Between 1500 and 1800, alcohol became embedded in everyday European life. Beer and wine were staples, distilling made strong spirits cheap, and governments experimented with taxes and licenses. Coffeehouses and tea created new, sober spaces. This is how routine drinking tipped into what we now call “alcoholism,” or an alcohol use disorder, with a special focus on Europe and, more specifically, Britain.

Alcohol’s Shift From Celebration to Daily Fuel

Alcohol had always been part of European life. During the early modern period, it became part of the workday and the household. Brewing scaled up. Distilling moved from the apothecary to the marketplace. Global trade delivered sugar and wine across oceans. Merchants, landlords, and governments discovered that alcohol could be stored, transported, taxed, and sold with fewer risks than many foods.

People often trusted beer and wine more than uncertain water supplies. Alcohol provided calories for laborers and a quick lift for anyone facing hard work, cold weather, or a long journey. By the eighteenth century, strong spirits were widely available, especially in growing cities. In that setting, heavy and habitual drinking became visible to authorities, writers, and physicians.

Beer, Bread, and the Workday in Northern Europe

Beer anchored the diet across northern Europe. Households brewed small, table, and strong beer for different moments of the day. Small beer was weak and hydrating. Table beer had moderate strength and paired with meals. Strong or October beer was rich and often seasonal. In towns and on estates, portions could be generous, and they were spread through the day. When those portions skewed toward stronger brews, the result looked a lot like chronic intoxication in modern terms.

Wine Belts, Fortified Wines, and the South

South of a rough line that ran from the Loire to the Black Sea, wine culture was deep and resilient. Ordinary wines filled jugs and barrels, while fortified wines such as sherry, madeira, and port traveled well and earned loyal markets in northern cities and Atlantic ports. At every stop, wine was easier to tax than raw grain and easier to preserve than many foodstuffs, which gave governments a fiscal reason to encourage production and sale.

The Distilling Revolution

Distilling changed the tempo of intoxication. Brandy, rum, and grain spirits such as genever and gin concentrated alcohol into compact servings that could be retailed quickly and cheaply. Dutch, French, English, and Iberian traders built profitable circuits that linked vineyards, grain fields, sugar plantations, and urban markets. Spirits offered the highest dose per coin and did not spoil easily. Urban poverty, seasonal unemployment, and the street-level dram shop created a new pattern of quick, solitary drinking that worried reformers and magistrates.

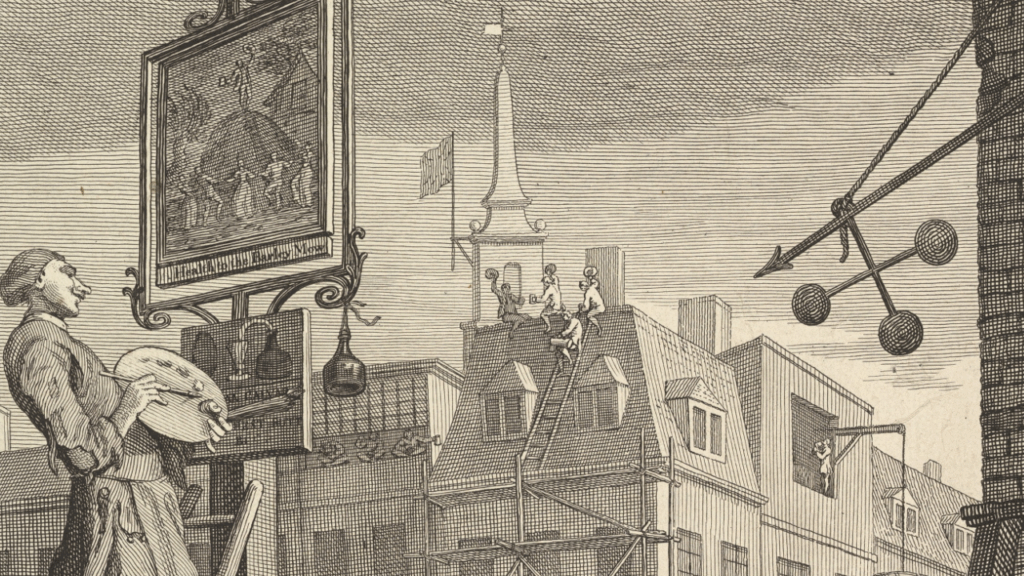

Britain’s Gin Craze and What the Government Tried

Britain offers the clearest case of policy responding to runaway spirits. In the early eighteenth century, cheap gin spread through London and other towns. Public prints and sermons linked gin to neglect, crime, and disorder. Parliament tried to choke the trade with a high retail license and heavy duties in the 1730s, and the measure backfired because evasion was easy and enforcement was weak. In 1751 lawmakers tried a different approach. They pushed spirits into the established licensing system, limited who could sell, and made enforcement more practical. Prices rose, outlets fell, and the worst of the crisis cooled.

The turning point was not only law. Grain prices, war, and better policing shifted incentives. Moral campaigns mattered in some parishes. Over time, the combined pressure of licensing, price, and policing reduced the most visible street-level harm.

Quick Timeline for Britain

- 1784: Tea duties are cut, smuggling declines, and legal tea consumption rises.

- 1550s: Alehouse licensing becomes part of local governance.

- 1650s to 1660s: Coffeehouses open in London and spread quickly.

- 1670s: A royal proclamation briefly attempts to suppress coffeehouses, then is withdrawn.

- 1730s to 1750s: Parliament experiments with gin control. A harsh tax and license approach falters, then a 1751 law uses licensing and distribution rules to curb street sales.

Coffeehouses, Tea, and a Different Daily Lift

As gin rose, stimulants created a competing daytime culture. London coffeehouses appeared in the mid-seventeenth century and quickly became hubs for news, trade, and talk. A royal proclamation briefly tried to suppress them in the 1670s, but it was withdrawn, and coffeehouses stayed. By the late eighteenth century, tea duties were cut, smuggling waned, and legal tea grew cheaper. Coffee and tea offered warmth, stimulation, and sociability without intoxication. That mattered for clerks, artisans, merchants, and others who needed a clear head during the working day.

Coffeehouses and Tea as Sober Alternatives

- Coffeehouses offered news, trade, and conversation with caffeine instead of intoxication.

- The state tried to limit them once, then backed down.

- Later tax reform made tea cheaper and legal, which encouraged daily stimulant use without impairment.

What Counted as “Alcoholic” Then Versus Now

Modern public health uses a standard drink. In U.S. terms, that is about 14 grams of pure alcohol, roughly one 12-ounce beer at 5%, one 5-ounce glass of wine at 12%, or a 1.5-ounce shot of spirits at 40%.

Early modern drinkers did not speak that way. They spoke of small, table, and strong beer, ordinary and fortified wine, and proof spirit. British proof later standardized at a little above 57% alcohol by volume for taxation. In practice, many commercial spirits were sold near what we now call 40%.

If you convert roughly, table beer looks like today’s pale ales. Strong beer overlaps with modern strong ales or imperial stouts. Ordinary wine sits at familiar strengths. Fortified wine sits above that range. Gin, brandy, and rum often match modern spirits. The difference was not the liquid alone. Serving sizes were larger in many settings, and drinking could be woven into every part of the day.

Converting Historical Drinks to Modern “Standard Drinks”

- Small beer, often 1% to 3% alcohol by volume. Twelve ounces is roughly half to two thirds of a modern U.S. standard drink.

- Table beer, often 2% to 4%. Twelve ounces is roughly one to one and a half standard drinks.

- Strong beer (also known as October stock beers), often 9% to 11%. Twelve ounces is roughly two to two and a half standard drinks.

- Ordinary wine, often 10% to 14%. Five ounces is roughly one standard drink.

- Fortified wine, often 16% to 20%. Three to four ounces equals roughly one standard drink.

- Spirits, commonly bottled near 40%. One and a half ounces equals one standard drink.

Contemporary tax/price classes distinguished small, table, and strong beer, and table beer was generally low to middling strength.

Spirits, Proof, and “Navy Strength”

- British 100 proof later equaled a little more than 57% alcohol by volume for tax measurement.

- Many commercial spirits were sold near 40%, which equals 70 British proof on that older scale.

- “Navy strength” is a historical term used for spirits around the mid 50% range, but the term is more of a modern name popularized by brands like Plymouth in the late 20th century.

Law, Ledgers, and Everyday Order

Alehouse licensing existed in England long before the gin panic. Tudor statutes put local justices in charge of who could sell drink, and that tradition of licenses and excise created the framework that later contained street gin. On the Continent, municipal rules, guild privileges, and excise farms served similar purposes. States learned that alcohol revenue paid for soldiers, roads, and debts, which made sudden prohibition unlikely. The typical pattern was regulation and taxation, followed by targeted crackdowns when disorder became too visible.

Global Trade and the Price of Intoxication

Cheap spirits depended on global trade. Rum drew on sugar and enslaved labor in the Caribbean and the Americas. Fortified wines rode Atlantic winds to new consumers. Northern distillers turned grain surpluses into cash. As shipping and credit improved, the real price of strong drink fell for many urban consumers. Falling prices and dense retail networks made quick intoxication easier, especially for the poor. That economic story helps explain why moral campaigns alone rarely solved the problem.

From Moral Failing to Medical Concern

Preachers and magistrates had long condemned drunkenness as vice. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, physicians began to describe habitual drunkenness as a disease of the will and the nerves. The language of pathology grew while the word alcoholism entered print a little later. The label changed, but the underlying forces of availability, price, and routine still shaped harm.

Read more about modern twentieth century efforts to discourage “drunkenness” through groups like Alcoholics Anonymous here.

Why This History Matters for Recovery Today

Two lessons translate to modern drinking culture:

- First, availability and price drive harm. When strong drinks are cheap, ubiquitous, and loosely regulated, communities suffer.

- Second, culture and routine can pull in a healthier direction. Coffeehouses and tea give a historical example of alternatives that fit daily life.

Recovery support works better when communities and friend groups make nonalcoholic routines visible, social, and easy to choose.

If you’re looking for alcohol addiction help, Swift River in Massachusetts can help. Contact us today to discuss admissions.

Sources and Further Reading

- Fernand Braudel, The Structures of Everyday Life

- Peter Clark, The English Alehouse

- Jessica Warner, Craze

- James Nicholls, The Politics of Alcohol

- Brian Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee

- U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, standard drink definitions for modern comparisons.

- Richard W. Unger, Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

- John J. McCusker and Richard S. Dunn, on rum, sugar, and Atlantic trade, for the global price story behind spirits